[ez-toc]

Introduction

Summary

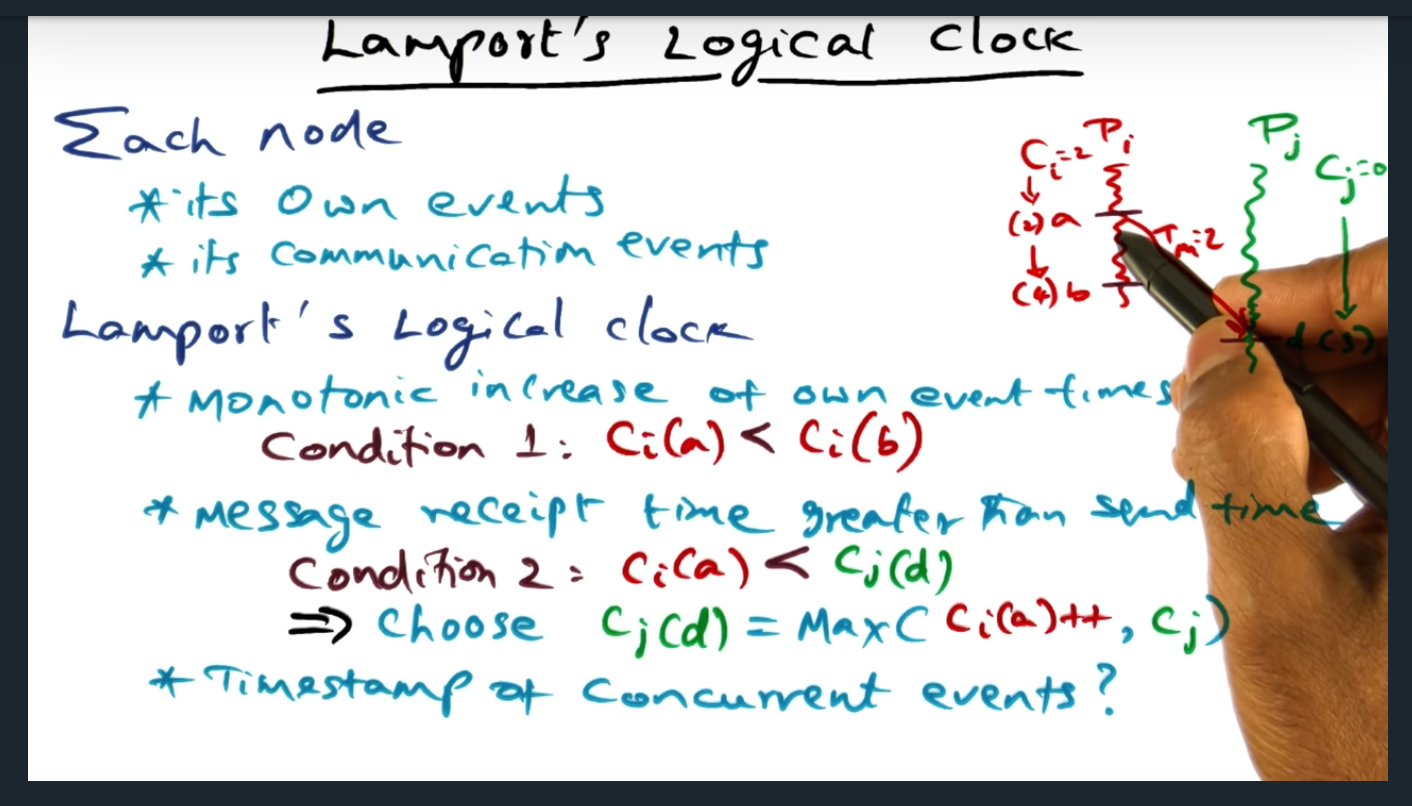

Now that we talked about happened before events, we can talk about lamport clocks

Lamport’s Logical Clock

Summary

A logical clock that each process has and that clock monotonically increases as events unfold. For example, if event A happens before event B, then the event A’s clock (or counter value) must be less than that of B’s clock (or counter). The same applies between “happened before” events. To achieve this, a process will increase its own clock monotonically by setting the counter to the maximum of “receipt of the other process’s clock or its own local counter”. But what happens with concurrent events? Will hopefully learn soon

Events Quiz

Summary

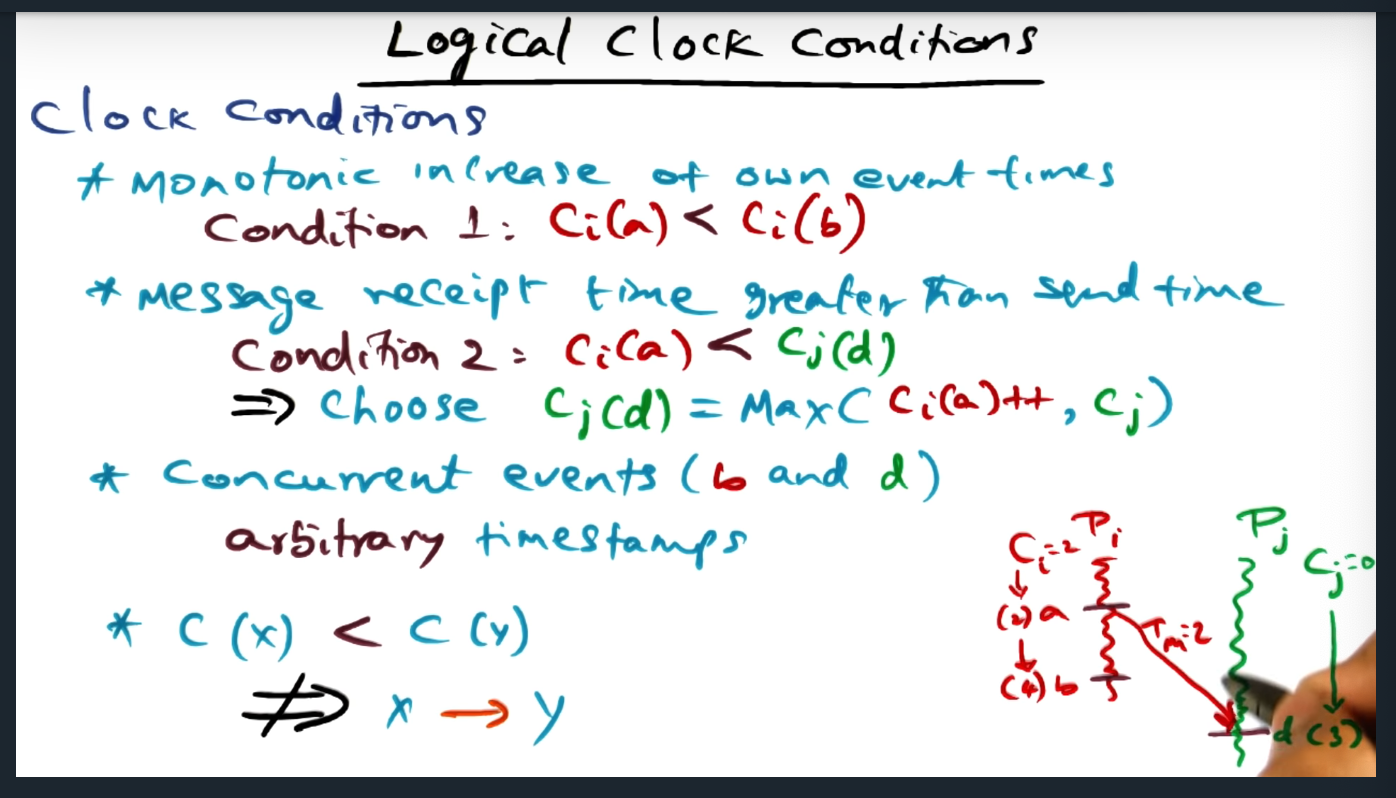

C(a) < C(b) means one of two things. A happened before B in the same process. Or B is the recipient and chose the max between its local clock.

Logical Clock Conditions

Summary

Key Words: partial order, converse of condition

Lamport clocks give us a partial order of all the events in the distributed system. Key idea: Converse of condition 1 is not true. That is, just because timestamp of x is less than timestamp of y does not necessarily mean that x happened before y. Also, is partial order sufficient for us distributed system designers?

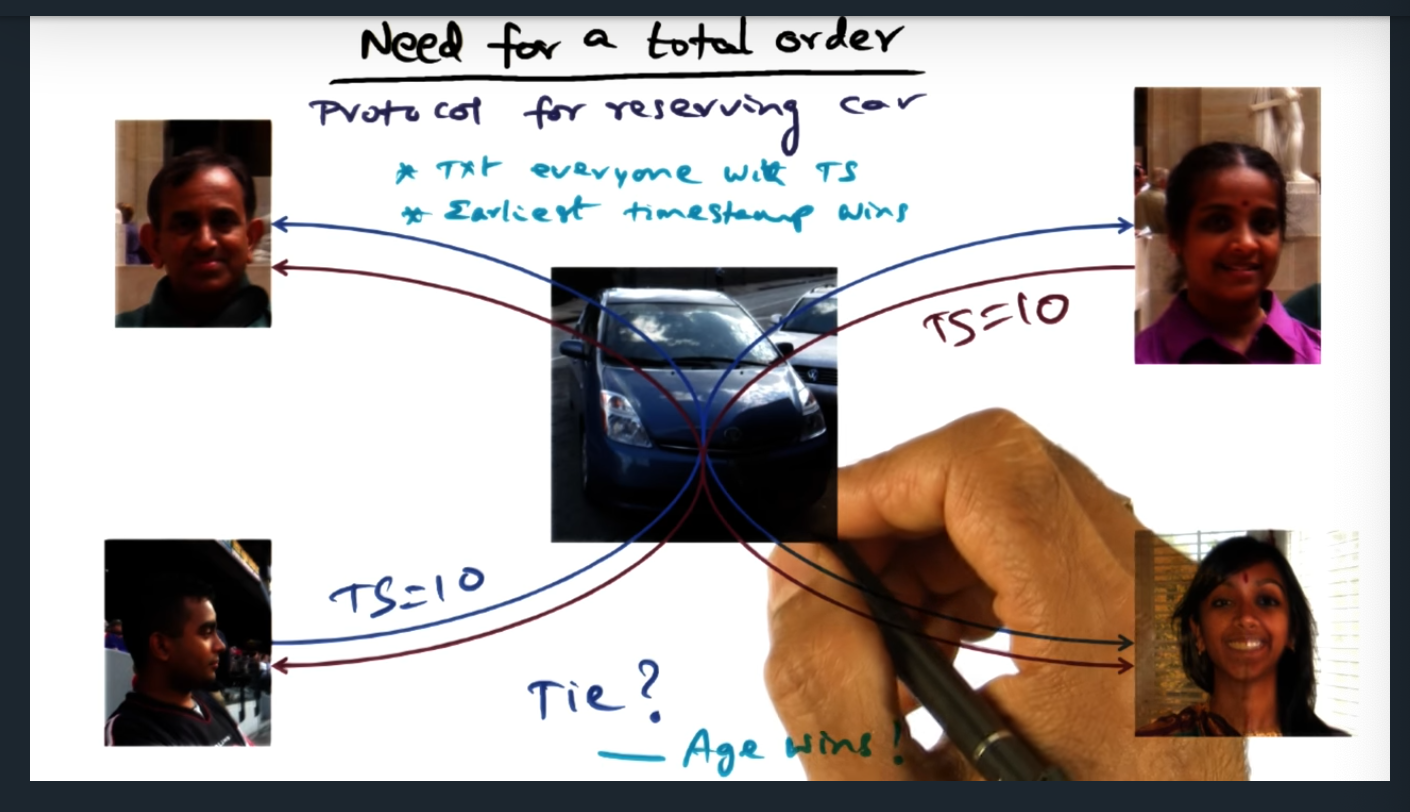

Need For A Total Order

Summary

Imagine a situation in which there’s a shared resource and individual people want access to that resource. They can send each other a text message (or any message) with a timestamp. The sender with the earliest timestamp wins. But what happens if two (or more) timestamps are the same. Then each individual person (or node) must make a local decision (in this case, oldest age of person wins)

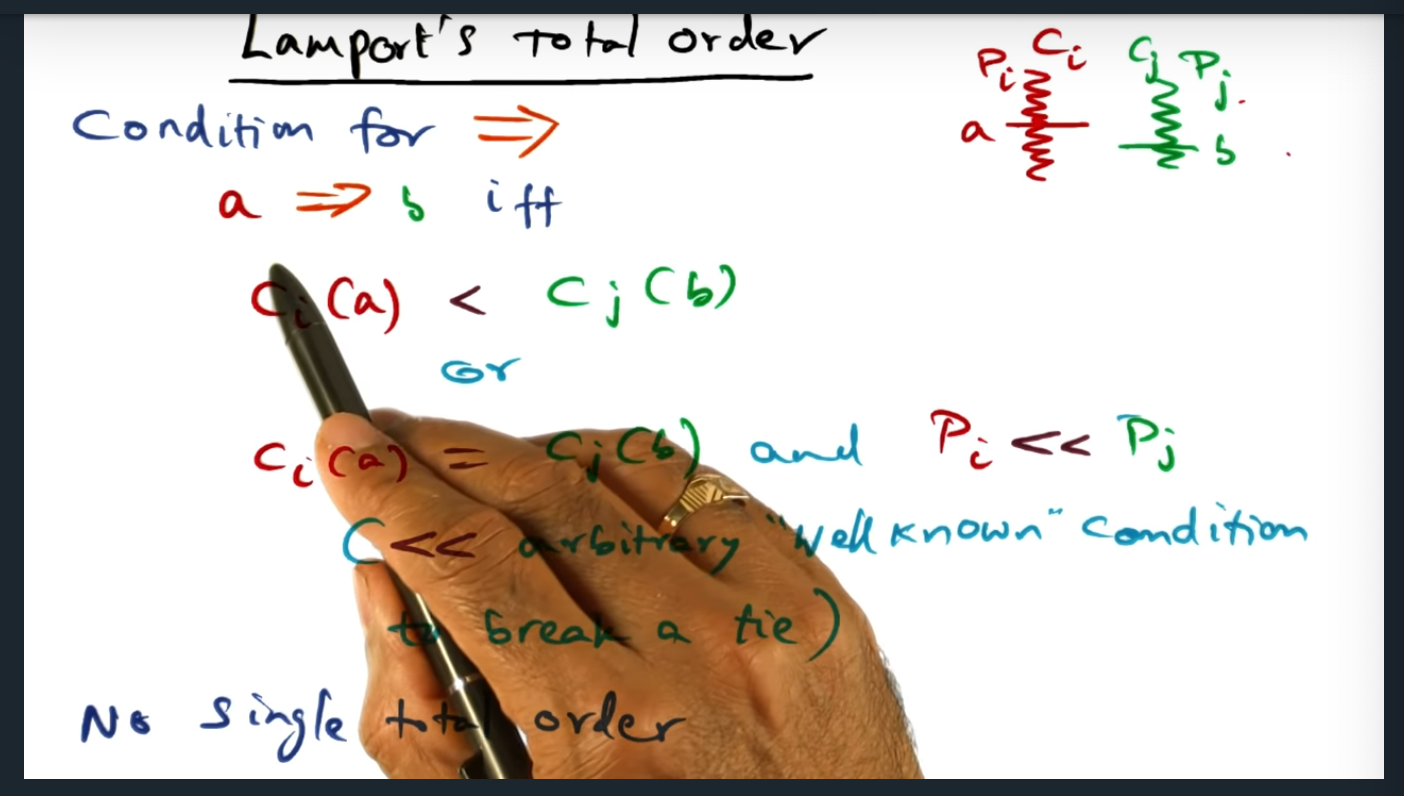

Lamport’s Total Order

Summary

Use timestamps to order events and break the time with some arbitrary function (e.g. oldest age wins).

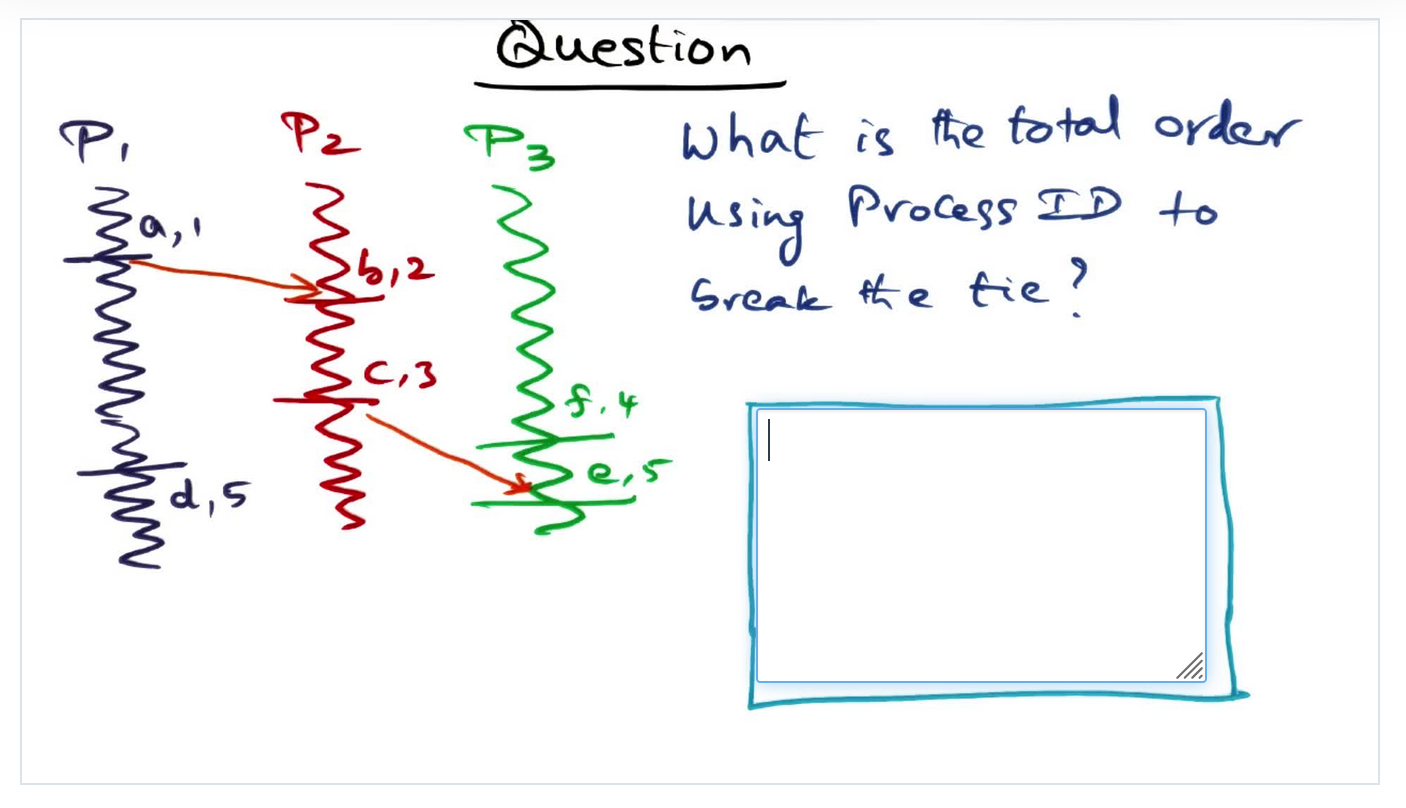

Total Order Quiz

Summary

Identify the concurrency events and then figure out how to order those concurrent events to break the ties

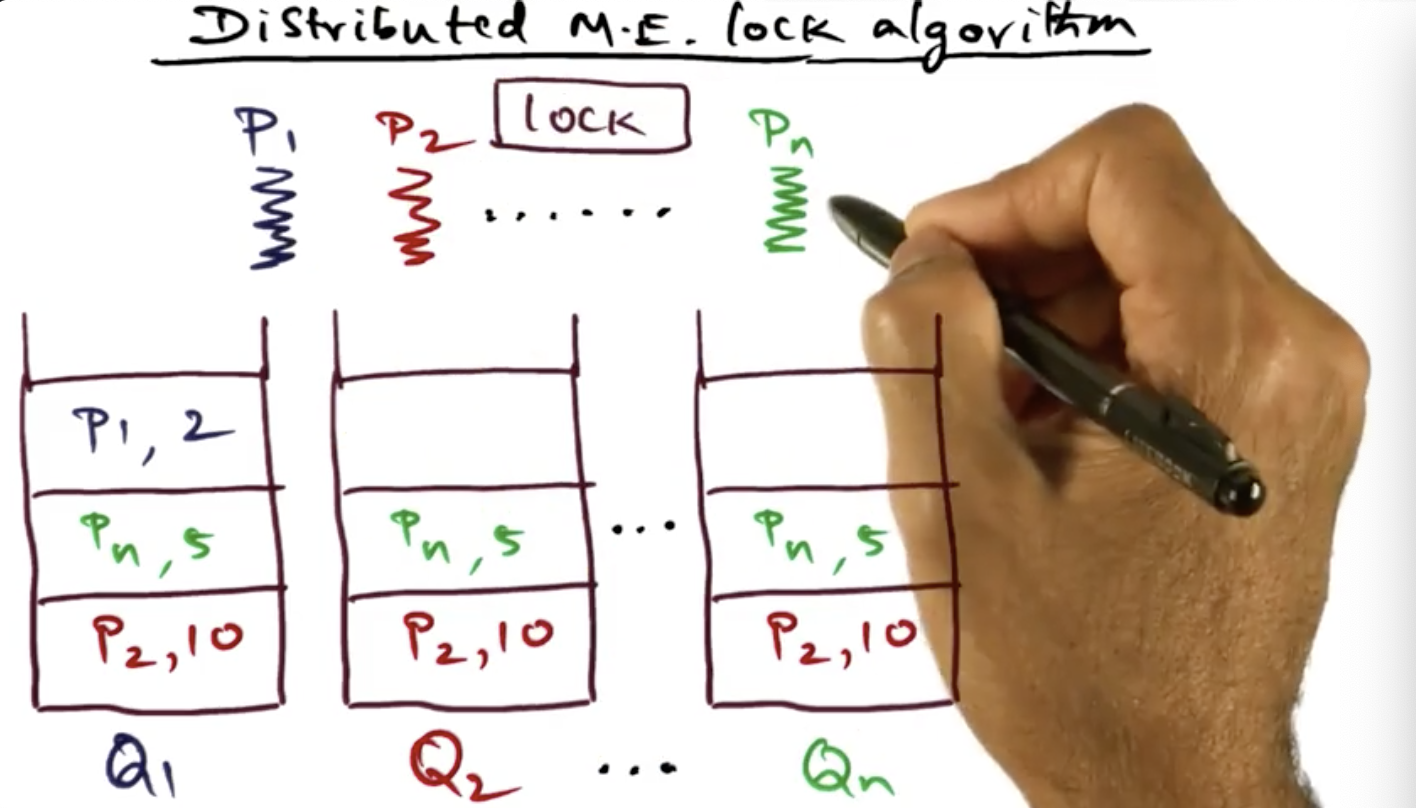

Distributed Mutual Exclusion Lock Algorithm

Summary

Essentially, this algorithm basically requires each process to send their lock requests via messages and these messages need to be confirmed by the other processes. Each request contains a timestamp and each host will make its own local decision, queueing (and sorting) the lock request in their local process and breaking ties by preferring lowest process ID. What’s interesting to me is that this algorithm makes a ton of assumptions like no broken network links or split brain or unidirectional communication: so many failure modes that haven’t been taken into consideration. Wondering if this will be discussed in next video lectures

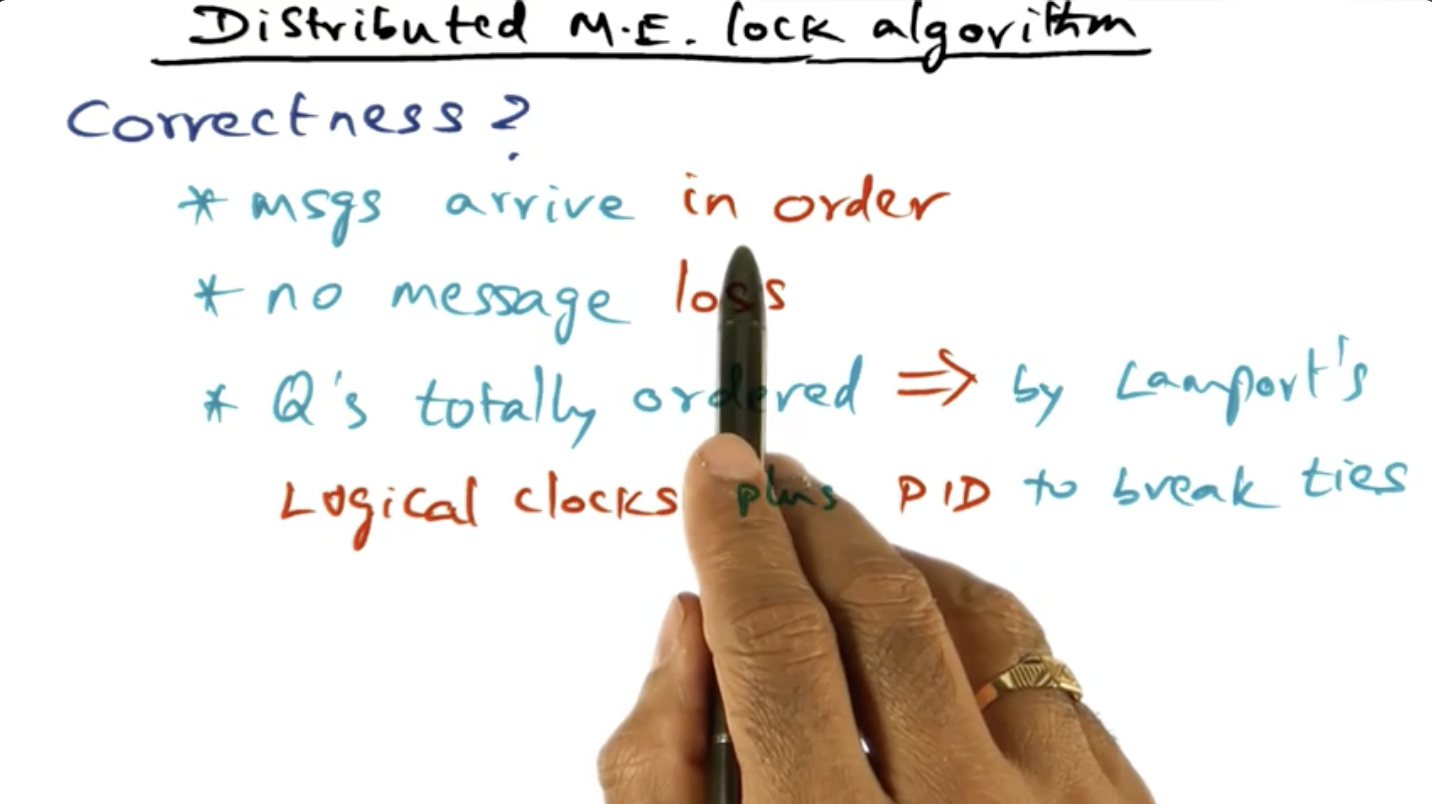

Distributed Mutual Exclusion Lock Algorithm (continued)

Summary

Lots of assumptions of distributed mutual exclusion lock algorithm including 1) All messages are received in the order they are sent and 2) no messages are lost (this is definitely not robust enough for me at least)

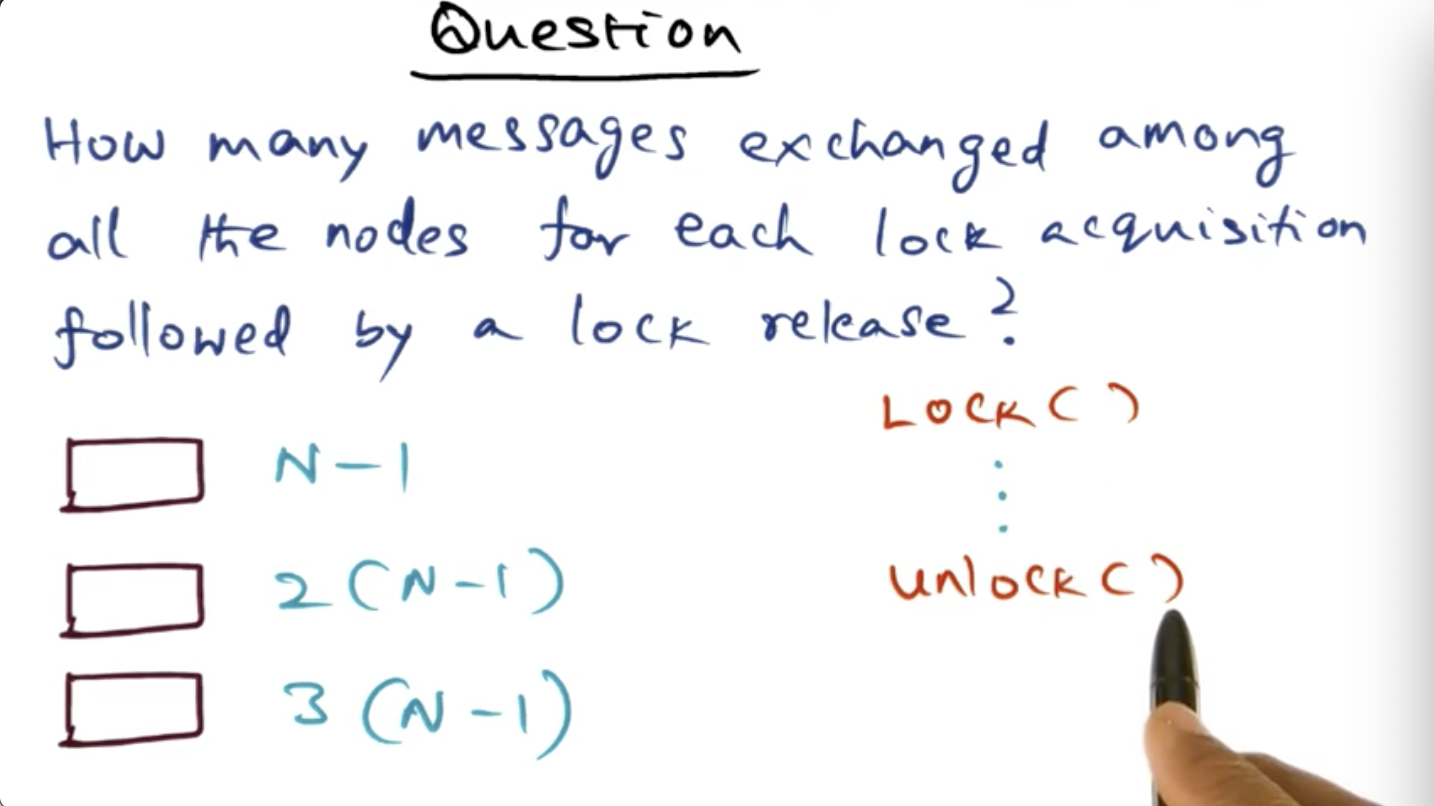

Messages Quiz

Summary

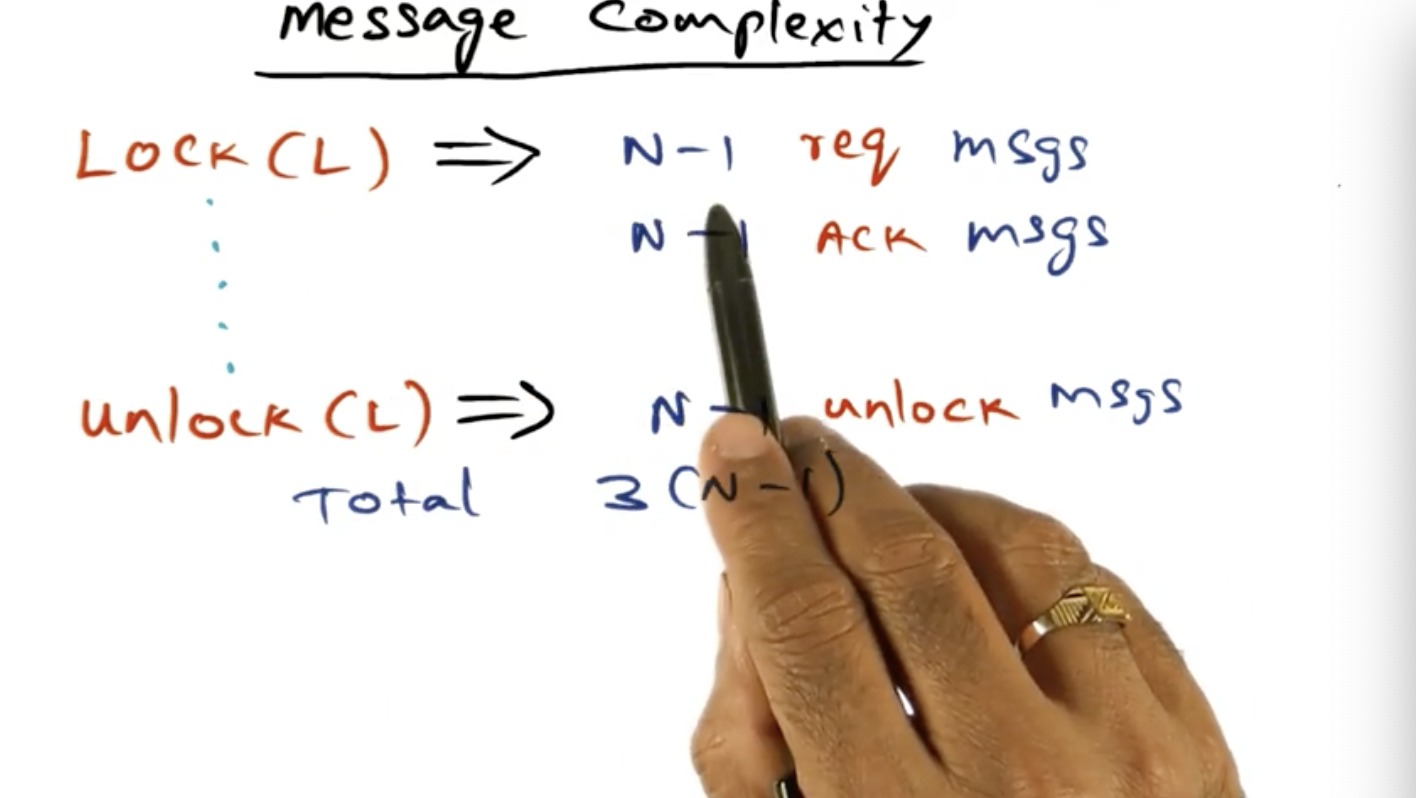

With Lamport’s distributed mutual exclusion lock, we need to send 3(N-1) messages. First round that includes timestamp, second for acknowledge, third for release of lock.

Message Complexity

Summary

A process can defer its acknowledgement by sending it during the unlock, reducing the message complexity from 3(N-1) to 2(N-1).

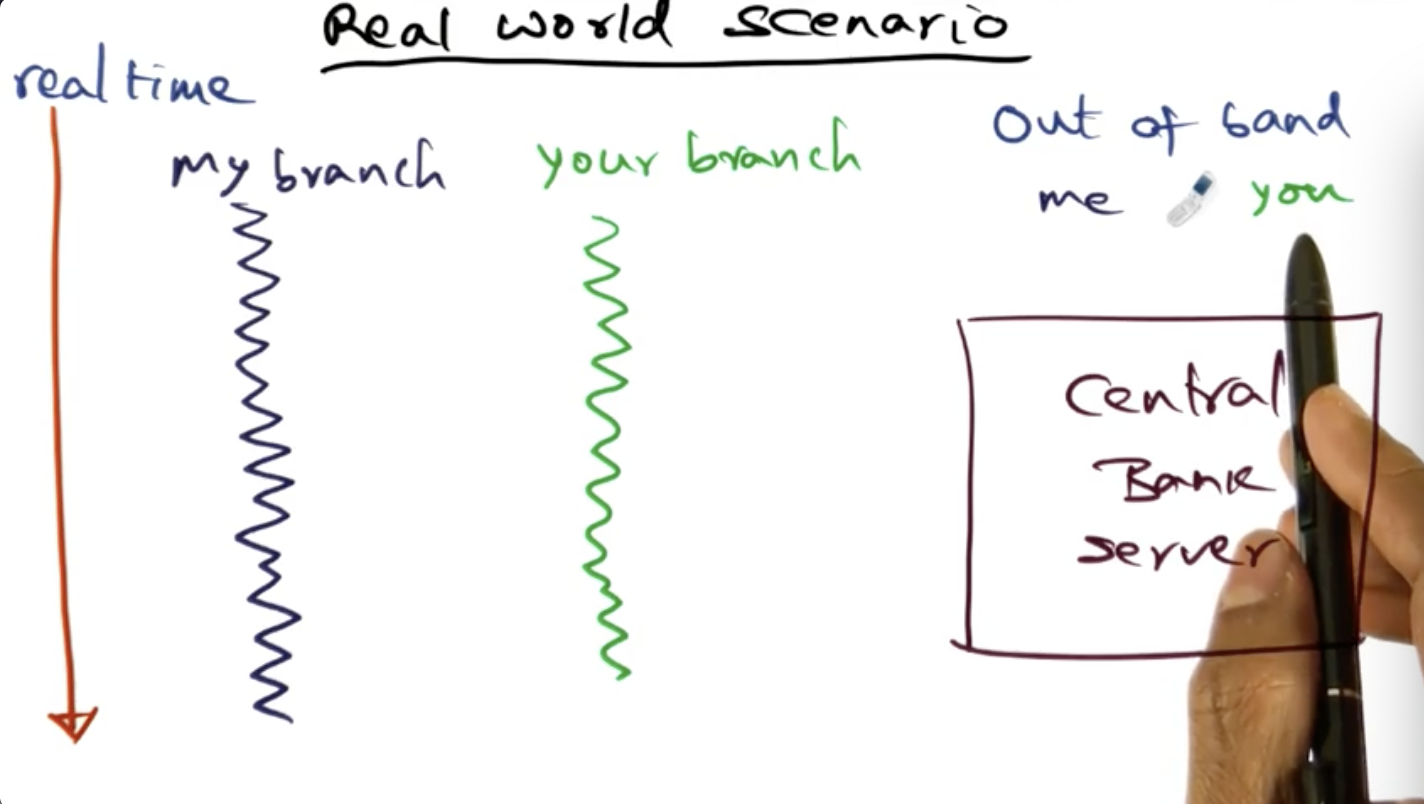

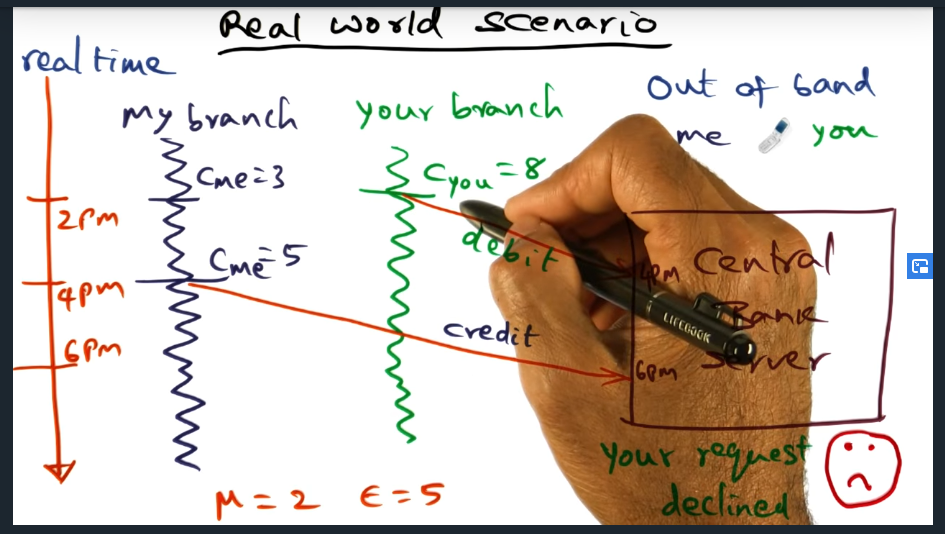

Real World Scenario

Summary

Logical clocks may not good be enough in real world scenarios. What happens if a system clock (like the banks clock) drifts? What should we be doing instead?

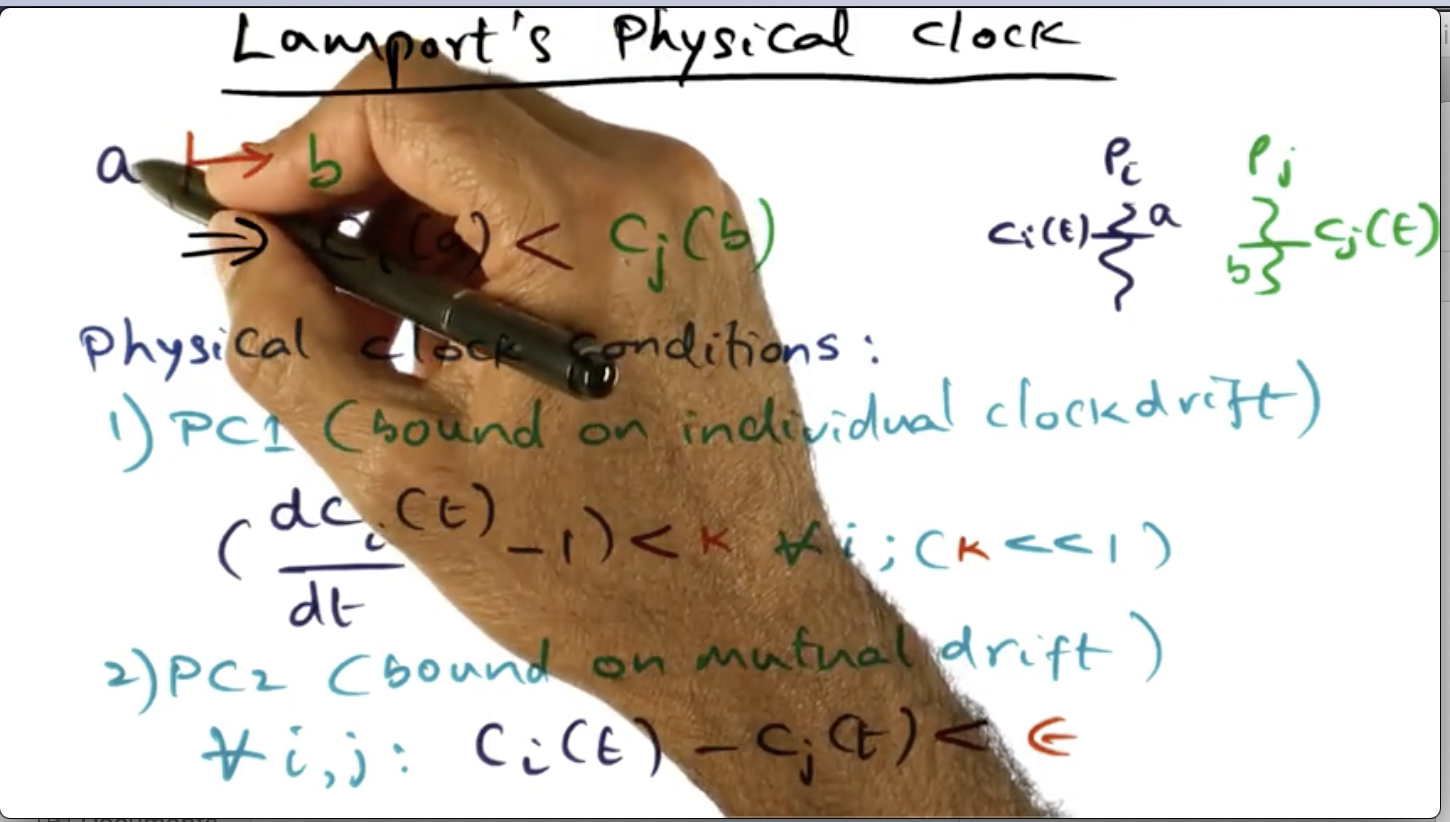

Lamport’s Physical Clock

Summary

Key Words: Individual Clockdrift, Mutual Clockdrift

Two conditions must be met in order to achieve Lamport’s physical clock. First is that the individual clock drift for any given node must be relatively small. Second, the mutual clock drift (i.e. between two nodes) must be negligible as well. We shall see soon but the clock drift must be negligible when compared to intercommunication process time

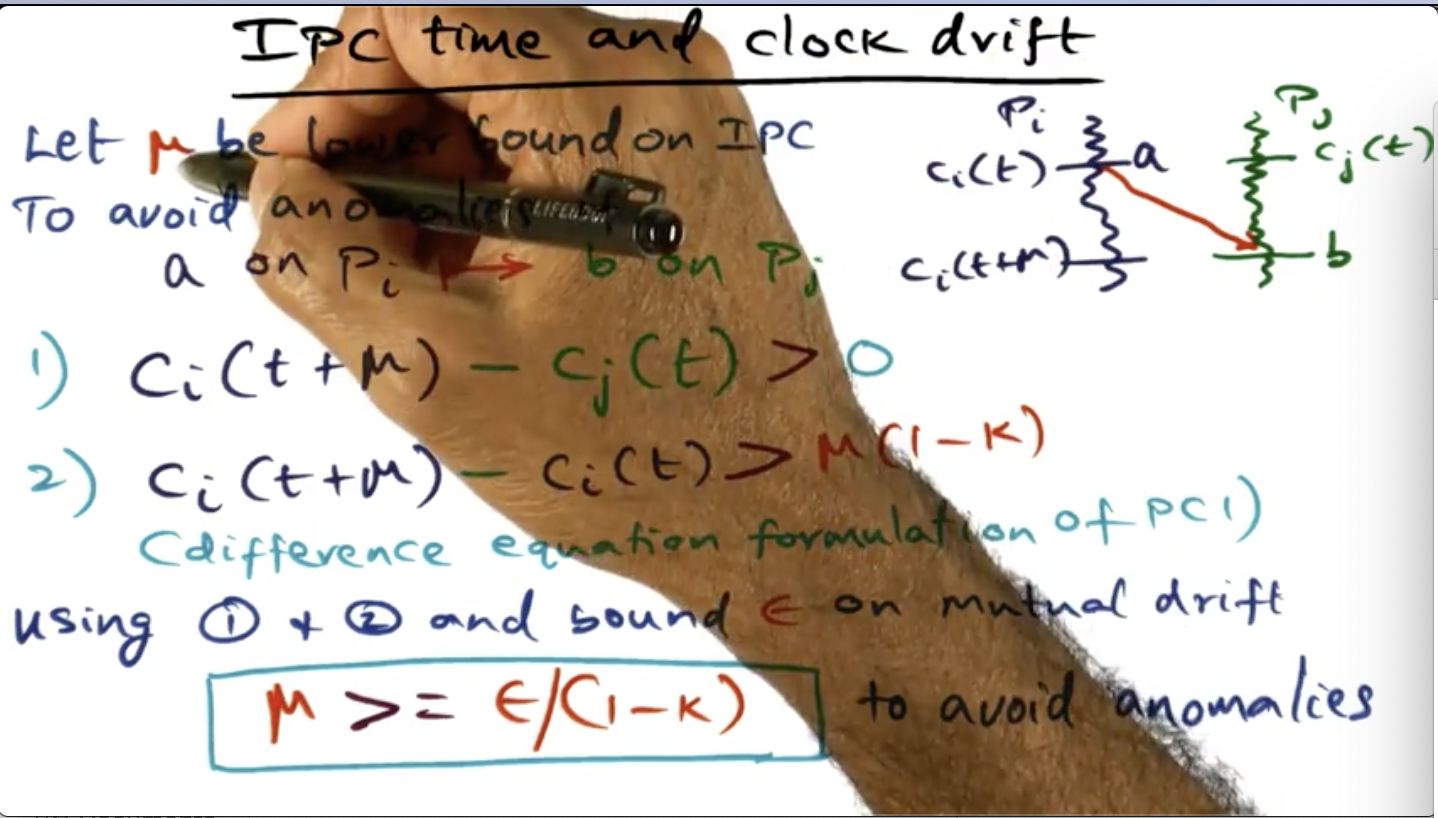

IPC time and clock drift

Summary

Clock drift must be negligible when compared to the IPC time. Collectively, this is captured in the equation M >= Epsilon ( 1 – k) where E is the mutual clock drift and where K is individual clock drift.

Real World Example (continued)

Summary

Mutual clock drift must be lower than IPC time. Or put differently, the IPC time must be greater than the clock drift. So the key take away is this: the IPC time (M) must be greater than the mutual clock drift (i.e. E), where k is the individual clock drift. So we want a individual clock drift to be low and to eliminate anomalies, we need IPC time to be greater than the mutual clock drift.

Conclusion

Summary

We can use Lamport’s clocks to stipulate conditions to ensure deterministic behavior and avoid anomalous behaviors